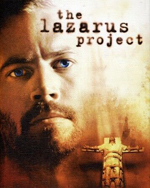

In his excellent novel The Lazarus Project, Bosnian-born author Aleksandar Hemon combines historical, personal and fictional elements (in multiple narratives) to portray the overarching human experiences of exile, migration, alienation and loneliness.

The narrator feels at time isolated in his marriage to a woman he professes to love deeply; with the gulf created by their very distant cultural worlds and experiences he often finds himself feeling “unseen.” The following are two selections from Hemon’s novel (with my brief introductions).

* * *

The narrator, like the author, is a Bosnian immigrant to the United States, living in Chicago. He describes his wife Mary, “a full-blooded America”:

A full-blooded American, she was. She took me to baseball games and held her hand on her heart to sing the anthem, while I stood next to her, humming along. She used the national we when she would say, “We are a nation of immigrants.” She often craved cheeseburgers.

George and Rachel [her parents] had bought her a car for her sixteenth birthday. She had the bright, open face that always reminded me of the vast midwestern welkin. She was routinely kind to other people, assumed they had good intentions; she smiled at strangers, it mattered to her what they thought and felt. She was often embarrassed; she dreamt of learning a foreign language; she wanted to make a difference. She believed in God and seldom went to church.

On a visit to Vienna on their second anniversary, where he is able to share some of his own history and past in a more immediate way, in an environment closer to his own roots, he feels closer to Mary.

Love was what I had felt for Mary when she took me to Vienna for our second anniversary, just weeks before 9/11. She had booked a fancy hotel with gilded convolutions on the walls and ceilings; she had Googled the best restaurant in town, bought a suit for me and a chancy red dress for herself to wear for the anniversary dinner. After the dinner, we roamed Vienna, we held hands, the hands were warm, the night was cool, the street lights glinted.

I told her about my family and the Empire and their journey to Bosnia, a story she had heard before, but this time it seemed that everything around me was evidence that I had not made it up. Now she had to believe me, that I had had a life, that my family had a history, but it was all connected through a powerful and loving, if perished, empire.

We were walking down the Main Strasse, whatever you call it, with a lot of modern shops she would have been interested in had I not been so compelling, when, as if on cue, we heard an angelic voice singing the Ukrainian song my grandfather liked to sing. The singer must have been trained: he rounded his mouth and breathed like a pro, but he was blind, holding a tall white cane in front of himself like a biblical staff.… The song was a heartbreakingly sad one – Ridna Maty Moya it was called: My Sorrowful Mother.

We stood there, squeezing each other‘s hands as though trying to press through the flesh to the bones and then beyond. She kissed my cheek and neck, and I felt the joy of omnipresent love –- everything around me speaking about me with affection, and Mary was listening.