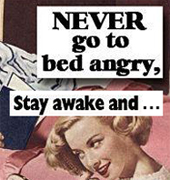

I am not a very good sleeper. Going to bed upset or overwhelmed can keep me up and tossing until 3 a.m. You might think, then, that I would welcome the imperative that one should resolve all disagreements before settling down for the night. Should I perhaps be heeding the wisdom in the New Testament verse — “Let not the sun go down upon your wrath” (Ephesians 4:26) — often quoted as the source for this entrenched belief?

There are, indeed, studies that support the notion that sleep “protects” (rather than dissipates) the emotional response (see: The Journal of Neuroscience, Jan. 2012); others suggest that sleep, perhaps as an evolutionary mechanism, may even enhance emotional reactivity. I am, however, a realist, looking for pragmatic approaches for myself and my clients. Most of us can not solve problems — with a spouse or family member — when we are angry or flooded.

Flooding refers to our brain’s physiological response to danger: Our hearts begin to pound, our hands to shake, and our capacity for concentration or rational problem-solving flies out the window. In the face of what our brain is perceiving as danger, the reasoning center of our brain — the prefrontal lobes in the front — shuts down, and our more primitive, reptilian brain takes over. We then enter into “fight or flight” mode, in which our vision is tunnel at best.

Writes John Gottman, Ph.D., professor emeritus of psychology at the University of Washington and author of The Seven Principles for Making Marriage Work: “The idea that it’s helpful for couples to air their grievances in the heat of the moment is probably one of the most dangerous marriage myths out there… Often, nothing gets resolved — the partners just get more and more furious.”

Forcing a physically and emotionally exhausted partner to thrash out an issue into the wee hours of the night just doesn’t make much sense. Perhaps more relevant, it doesn’t work. Waiting instead until the next morning, the next day, or even the day after that, when both partners can calmly process and put to rest the issue or conflict at hand is is often much more effective. In addition, waiting until both are calm and able to work through the issue transmits a powerful message of trust in the strength of the relationship to survive the uncomfortable night.

The same respect should be afforded to children. Allowing for individual time frames in how long it takes different children to calm down is a powerful validation that emotions are okay. Without tolerating irresponsible demonstrations of emotions (emotionally or physically abusive behavior), we can still convey to our children that we trust in their ability to process the particular problematic interaction later that day, the next day, or when the fire has died down. Forcing them to apologize and “make nice” by sundown when they are still feeling hateful inside is likely to be more confusing than educational.

A final note about sibling rivalry: Children do tend to calm down more quickly than do adults; they seem to be able to move relatively quickly from an intense sibling battle into peaceful joint play. Insisting that the instigator apologize — a particularly slippery slope given how impossible it is to determine who the instigator was, and given also how siblings often use such battles to get parental attention — is sure to fuel the flames. Instead, removing ourselves from the battleground will more likely draw them back towards one another in no time.